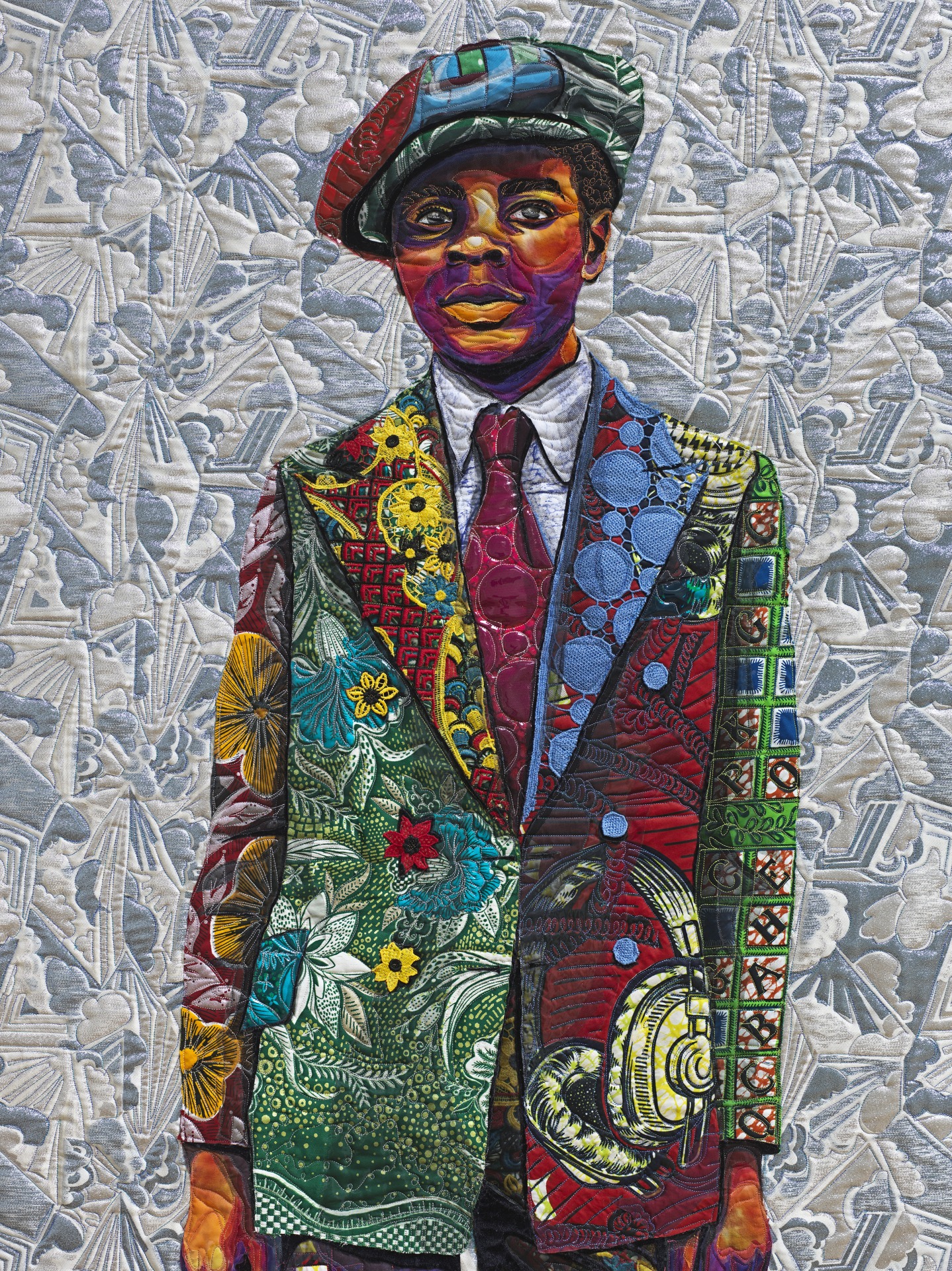

“I am searching for images that remind me of my childhood and of people I could have known.” That’s the mission that drives Bisa Butler, the artist whose quilted portraits are currently making a splash with her exhibition The World Is Yours at the Jeffrey Deitch Gallery in New York City. “As Black people who were born on this continent, who either came from a colonized or enslaved place, we have loved ones who are lost," says Butler. "There is a longing there I'm responding to.”

Her response comes through in her creations. Crafting anonymous faces and celebrity renderings from fine fabrics and embellishments, she seamlessly weaves the materials together to create intricate and mesmerizing reflections of humanity.

Here, the gracious and brilliant artist reveals what spurred her love of quilting and shares the emotional journey of creating her art.

EBONY: How did you start making all these incredible quilts?

Bisa Butler: I was a Newark public school teacher for about 15 years, where I was making art all this time. We as Black women support each other. All my teacher friends have quilts. They would ask if I could make them one, even if they just paid me a little bit of money. I always charged though, because my mother told me you have to charge people for your work. This is a labor, not a hobby.

What was the turning point for you to step out and become a full-time artist?

The librarian in our building had passed—she was late to school one day and had died in her sleep. The school had a moment of silence for her. I taught teenagers who, after about 30 seconds of silence in her honor, just moved on from it. At that moment, my mind shifted and I thought if you want to be an artist, you're going to have just to do it, you don't have forever. None of us know what our story is going to be and if you do pass unexpectedly, they're gonna move right on without you. My art career didn’t happen right away. I had an exhibit in Morristown, New Jersey, with the Black civic group Art in the Atrium, LLC. Then I had an exhibit with Richard Beavers Gallery in Brooklyn, New York. I have been showing at Black galleries around the country, not solo shows, but just one piece, for years. Now I’m working with the Jeffrey Deitch Gallery—so it took about 25 years.

How did you learn quilting? Is it a family tradition that’s been passed down from generation to generation?

My mother and grandmother were quintessential Black women: we like to look good and we like fine things. Presentation is everything, and for the older generation, it was wearing gloves and all of that. My grandfather was a professor and worked for the Foreign Service, so he got a position in Morocco in the 1950s. This ordinary Black family from Orange, New Jersey, is suddenly moving their 10 kids to Morocco. And my grandmother, my mother and my aunts looked at Vogue and French magazines. They would see a Christian Dior dress and they would replicate it six times for all the girls. They knew how to sew very, very well. When I was in school, I thought I should be a painter, and a painter paints, right? They have a beret. They wear striped shirts. They're painting outside by the water. But that's not really what I like to do. In my free time, I was upcycling clothing and making "mommy and me" outfits for me and my then toddler daughter. A professor said, “Bisa, you should add fabric to your paintings.” I went to grad school and learned about quilting. I thought, “Oh good. I don't need to paint. I can make quilts and portraits and use what I love.” I love going to the fabric store. All the things there are just so glittery and tactile, the sequins and silk. It’s so much sensory. So quilting was the perfect combo between my hobby and what I went to school for.

What is the meaning and motivation behind your work?

I find myself drawn to compelling photos of African American people. I’m interested in what makes people tick and what’s in their heart. I find people interesting. I always saw the good in my students—even if they were acting out—to know who that child really is and what's going on in their life and still see the beauty in that child. I look for that in photographs. There can be an interesting gaze; it can be intense, loving or sweet. And I'm searching for images that remind me of my childhood and of people I could have known. I think it's not just me who does that. We have loved ones who are lost. And there's a longing there I'm responding to. I look at older photos and I wonder if am I related to this person. I could have already quilted images of my relatives or your relatives. There is a missing piece, I think, in the hearts of a lot of Black people. And I think when we see my quilts of an unknown person, it can hit on a memory that makes people feel something.

Tell us about the materials you use in your quilted art.

I learned to quilt in college, simple basic quilting which has a back, middle and top. I use the fabrics that my mother and grandmother used. That's why you see silk and lace and beads and rhinestones because I didn't learn to quilt from a quilter. They use cotton and flannel, durable fabrics that can be washed and put on your bed. I'm coming from dressmakers so mine are more delicate.

Your new exhibit in New York City is at a historic gallery.

Yes, and Jeffrey Deitch is a very historic gallerist. He was good friends with Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat; he used to sell Basquiat's work when the artist was alive. Jeffrey worked with a lot of street artists like Basquiat. There’s always been a stigma about graffiti artists and people who didn't go to art school. But now, some non-Black galleries are jumping on the bandwagon with the current trend of showcasing Black art. I'm glad my current gallery worked with Black artists before it was cool.

How many quilts do you think you've made over the course of your 25 years?

That is such a hard question. I went to a gallerist in Harlem years back and he was so cruel to me. He wasn't interested in my work or quilts. But he told me that [artist] Romare Bearden said, if you hadn't made 100 pieces of artwork, that you weren't an artist at all. I'm sure I've made more than 100 quilts by now. They weren't always big. When I was teaching, I could make a little one, eight by 10 inches. And the average size I used to make was a poster.

Is there one quilt that emotionally touched you when you made it?

There are a few like that. I made a portrait of the Harlem Hellfighters who were World War I soldiers. It’s my largest piece, about 13 x10 feet, and was purchased by the Smithsonian. It features nine of the Hellfighters. If you've ever seen that photo, they're fine. I mean, they're fine, fine. They're these young men on the ship about to come into the New York harbor for a ticker tape parade. They literally have saved the world and you can tell they know it. Their coats are shiny. The haircuts are tight. They probably haven't seen their mothers, fathers, wives and girlfriends for a few years because they've been over in Europe and they survived. The Hellfighters were the 369th regimen out of New York and they were mostly Black and Puerto Rican. They were in the front longer than any other unit and had the most casualties. They didn't have any prisoners of war because their officers told them they fight or die because the U.S. Army was not going to negotiate to get them back. White American soldiers wouldn't fight next to Black men. Racism went all the way to the battlefield, and as we know, racism can follow you to death. White men were misinformed. They were told that Black men could not make the right intellectual decisions on the battlefield so they wouldn't want this person next to them. The French needed soldiers, and that's one of the places the Hellfighters fought quite heroically. I quilted my design in 2020 during the struggle of the pandemic. I had lost a friend and it was just really difficult to finish. It took about a year. I had read up on the Hellfighters and what they went through—the United States Congress just awarded the Hellfighters the Congressional Gold Medal in 2021. It took over 100 years for them to get their due from the American government. My husband said, “How did you expect this to be easy when you're doing a quilt called the Hellfighters?” I felt that it was a duty that I had to do and in the end; I felt really close to each young man.

What portraits do you want to do next?

There are so many historical photos I’d like to do. I've never done a James Van Der Zee photo. I talked to photographer Jamel Shabazz and we're gonna collaborate together. I haven't even touched the tip of my finger on the photographers from the diaspora. There were some amazing photographers from Mali and Nigeria in the 1960s. I just learned of the Windrush community, Jamaican immigrants who came to Britain in the1950s and took beautiful photos of their people living and working in London. With many amazing photographs as there are in the world, I won't be able to make them all. But I'm preparing for a show in 2025 with a big museum in Washington, D.C., so that's going to be really exciting.

Bisa Butler, The World Is Yours, on display at Jeffrey Deitch Gallery in New York City through June 30, 2023.