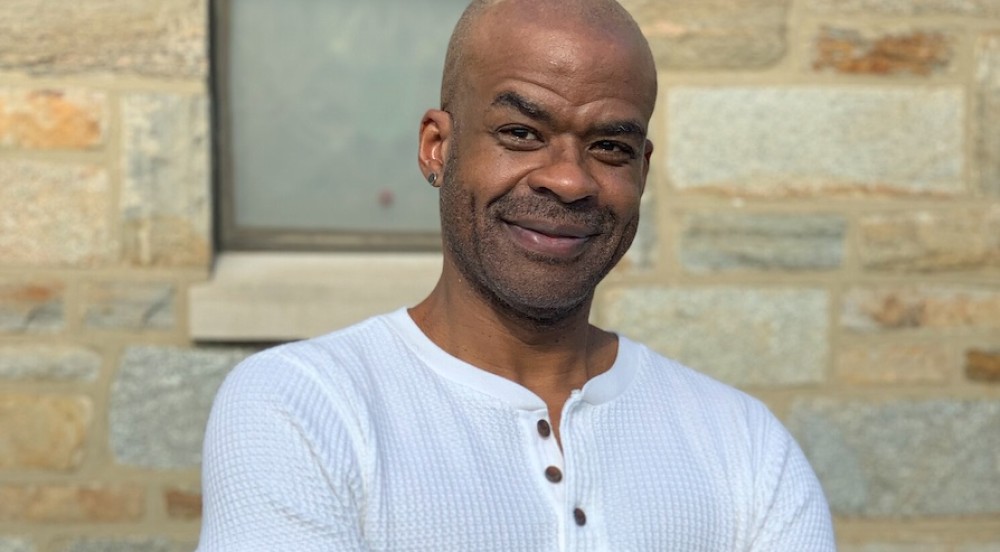

His impactful first novel will also be brought to life as an upcoming feature film

Novelist Brendan Slocumb’s playlist may include rock, hip hop, R&B—and yes, bluegrass—but his heart belongs to classical music. The violinist-turned-author’s fealty to the genre plays out measure-for-measure in The Violin Conspiracy, a spellbinding first novel that melds classical music, the mystery surrounding a stolen violin and history, too—by way of some troubling insights into our nation’s painful legacy of slavery.

So why build the narrative of this who-done-it around music? Because the author credits it as being both his salve and his salvation.

“Music completes me. It is satisfying in every way possible. It tops off my soul and it's just done so much for me—it saved my life. It’s taken me to college and around the world," he shares. "Music is everything, without it I know I would be either in prison or dead. One of the two.”

Instead, his passion for the art form led the Fayetteville, North Carolina-bred author to becoming an orchestral performer and an educator. “I have been a public and private charter-school teacher for 23 years,” he says, teaching “general music, strings, and guitar.” Also, he adds, “I teach privately—I give piano and violin lessons to kids and adults.” Now residing in D.C., Slocumb plays in a local symphony in Virginia, and even manages to find time to mix it up as a singer in a rock band called Geppetto’s Wud.

That appreciation for different forms of music is also a part of protagonist Ray McMillian’s makeup. Ray finds time to stoke his jazz jones as he strives to become a classical violinist of the first order. But the road to getting there will be a rough one. As a high school student pursuing the violin, he meets with several hurdles: financial hardship, bias and outright racism from instructors and peers, rejection and relegation by classical audiences, and most disheartening of all, an unsupportive family that undermines his dream at every turn.

But Ray is of a singular mindset and despite his rented instrument (the other students have their own) and lack of private tutelage he plays on. Despite his harridan of a mother constantly deriding him for practicing and pressuring him to quit school and apply for an hourly wage job to help her with expenses like a big-screen TV, he plays on.

Though Slocumb admits there is much of himself in Ray, he notes that art does not imitate life when it comes to his real-life relations. “It’s safe, and fair, to say that my family was nowhere near as difficult as Ray’s, but there was an aspect of just not quite getting what it was that I was so passionate about, but they would never actively try to stop me from learning violin or going to college—let me make that clear,” he underscores, with a laugh.

Unlike his other relatives, Ray’s grandmother is in his corner. Unfortunately, though, he sees her all too infrequently. But on a holiday sojourn from North Carolina to her Georgia home, a game-changing event happens. Grandma Nora gifts him with an old, beat-up violin pulled from her dusty attic and nestled in a tattered alligator case. The violin had once belonged to her grandfather, a former slave, who shared Ray’s gift for making the instrument come to life.

And Slocumb brings its magic to life for the reader as Ray plays it for the first time for his grandmother (and his recalcitrant family):

/ The melody started slow, in the night, a plucking of strings, snowflakes falling dreamily, one flake at a time; and then a burst of cold air poured down on them, and flakes eddied, biting in the chill, the north wind coursing through the living room. Dawn came, light glistening off a frozen pond. A bird flew down, hopped on new snow, looking for seed. Bare trees reached to the sky, achingly blue in the cold. …

He painted all this for them in the air, this first time, with the music from PopPop’s fiddle—of his own violin!—washing over them. How glorious this was to touch them, to make them hear, to give them this gift. /

The violin and the family history it represents becomes something of a talisman for Ray—especially after his grandmother passes—and an indelible part of his musical voice. While playing it, he catches the attention of Dr. Janice Stevens, a professor who recognizes his talent and helps him land a scholarship to her college.

Slocumb, who says his own college violin instructor mentored him in much the same way that Stevens does with Ray, emphasizes the importance of mentorship for developing musicians. He also stresses how important access is in bringing more diversity to the classical music field, which he says currently is just 1.8 percent Black.

“It’s a very sad statistic,” he notes. “I have never understood why that number is so low, because Black musicians are just like everyone else—we can play just as well. We know the repertoire. We have the technique—we do. We're just lacking the opportunity.”

With Stevens’ guidance, Ray’s talent flourishes and eventually he begins preparation for entering the famed Tchaikovsky competition. It is then that he takes his old fiddle for repair and restoration and discovers that underneath the age and built-on grime is a Stradivarius—an instrument worth million.

As word of this phenomenal find spreads and the media descends, so, too, do the vultures. Ray’s grasping family stakes a claim, as does another set of villainous players—the descendants of the slaver who once owned his great-great grandfather, who say that the instrument belongs to them. And, most devastating of all, while legal wrangling is underway and Ray is readying for the competition, his prized violin is stolen and held for ransom!

The pressure of losing his violin and rehearsing for the competition without it is monumental, especially while fending off micro and macro racist aggressions and trying to unravel the crime, but Ray soldiers on—continuing his rigorous practice schedule and keeping his eye on the prize. His grandma’s earlier advice seems prescient:

/ “You work twice as hard. Even three times. For the rest of your life. It’s not fair, but that’s how it is. Some people will always see you as less than they are. So you have to be twice as good as them.” /

This is a familiar mantra to African Americans, and if, as the axiom goes, “music is the universal language,” then Slocumb uses it to help speak some powerful truths about the Black experience—in classical music and beyond. And the seismic event that pushed him to write this book now is one that has impacted people around the globe.

“When I was writing the book and having people read it, some would actually say, ‘this is really over the top; things like this really don’t happen,’” reflects Slocumb. “During the summer of 2020, when the world saw what happened to George Floyd, I think that their eyes were opened. ‘Oh, you know, maybe things like this do happen.’ I felt that it was a good time for people to be aware of stories like mine. I hoped it was a good time to share these stories.”

One harrowing story from the book that occurs in Baton Rouge is born of a true-life experience, Slocumb says. According to the author, while on a road trip with a White friend in 2000 and driving his new Accord they decided to stay overnight in Baton Rouge en route to New Orleans. “I said to him, ‘We’re probably going to get stopped.’ He’s like, ‘Why would we get stopped?’

‘Because we’re in the Deep South and I’m in a brand-new black car,’” Slocumb responded. “He had no idea what I was talking about.” But sure enough after crossing a lane to make a left turn—signaling his intent, he adds—he gets pulled over: lights and siren.

“[The officer] gets on his bullhorn and tells me to get out of the car. My passenger gets to stay in the car. I have to get out, walk backwards, hands up, get down on my knees. He’s got his gun drawn. I think this is it, I’m done, it’s been a nice life. He makes me take my I.D out of my back pocket, walks up to me and looks at my driver's license and says, ‘OK, you can go.’" Slocumb asked, “Well what was all of this for?’ The response: 'Oh, you made an illegal lane change.’"

“So, this is what you do for an illegal lane change? Something tells me this is not what you always do,” the writer intones. “But I said I would never ever, ever go back to the city of Baton Rouge. If there was a bag of money with my name on it in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, it would just stay there. I’ll never go back to that city.”

In the book, Ray has an experience that is even more distressing while on his way to a concert, also in Baton Rouge. During that encounter, Ray, too, is forced to get down on the ground—in his performance tuxedo, no less.

The picture Slocumb paints of the incident is visceral in its indignity. And it’s one that may leap from the page to the screen in the near term. The author tells EBONY that the book has been optioned for a movie. “Sony bought the rights,” dishes Slocumb, “and I can say that George Tillman, from Soul Food—one of my favorites—has signed on to direct.”

Shining a spotlight on African Americans in classical music, or the lack thereof, and the grief and racism those few may have to endure is the resounding message of The Violin Conspiracy and Slocumb’s next book, too. And despite the obstacles he has faced in the field, he says he’d like to think he has one characteristic in common with protagonist Ray.

“I really like Ray’s resilience and the fact that he stays true to who he is. I like to think that that's an attribute that we share.”

To hear author/musician Brendan Slocumb talk more about music, check out his podcast How Music Can Save Your Life.