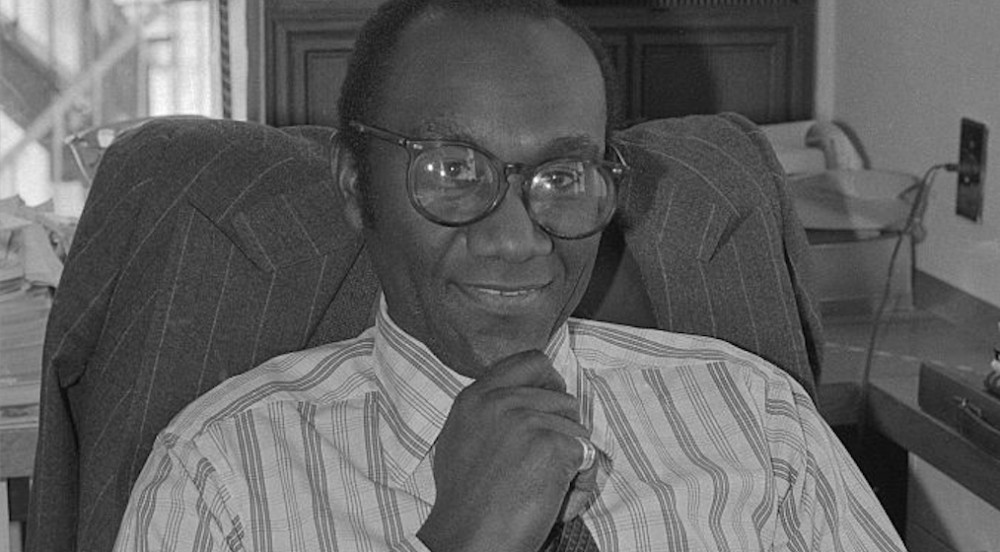

Franklin A. Thomas, who became the first Black person to run a major American philanthropic organization she he was president of the Ford Foundation, passed away at his home in Manhattan last Wednesday, the New York Times reported. He was 87.

Darren Walker, the current president of the foundation, confirmed his passing.

Born in 1934 to a hard-working West Indian family in Brooklyn, Thomas won an academic scholarship to Columbia University, becoming the first Black captain of an Ivy League basketball team, and set several school records for rebounds, two of which still stand.

After graduating in 1956 and serving four years in the Air Force, he returned to Columbia University for law school, receiving his law degree in 1963.

Thomas worked on housing law for the federal government and then with the U.S. attorney’s office in Manhattan before becoming a deputy commissioner with the New York Police Department. From there, he was appointed president of the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation, a product of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society legislation.

In 1977, Thomas left government to work in private practice and to run his farm in upstate New York. But he returned to public life after he accepted the invitation to become the first Black president of the Ford Foundation. Out of over 300 candidates, he was chosen to lead one of the most influential philanthropic organizations in the world, succeeding McGeorge Bundy in 1979.

“It’s an opportunity to build on this crazy, accidental combination of experiences I’ve had in an institution that’s potentially very flexible in its resources,” he said in 1979, after accepting the position. “The foundation can be an initiator of activities, open to risk‐taking. It can change directions without having to write new legislation.”

When Thomas assumed leadership, the foundation’s endowment which was $4.1 billion in 1973 had been reduced to $1.7 billion in 1979 and increasing inflation was bringing down the value of its existing grants.

In May of 1981, in what became known as the "Mother’s Day Massacre," he terminated over two dozen of the foundation’s leadership, including cutting “untouchable programs” and firing a collection of vice presidents known as “Bundy’s barons.”

“Frank Thomas saved the Ford Foundation,” Walker said. “We were spending ourselves into irrelevance.”

By the mid-1980s, things began to turn around as grants from the foundation were on the rise as well as the endowment.

When Thomas left his post in 1996, Ford’s endowment had grown to $7 billion and today it is valued at $16 billion.

Moreover, while at the Ford Foundation,Thomas used his power and influence to champion women’s rights. He insisted that women benefit from and lead all Ford-aided projects, not just those that were gender-specific. He increased the number of women in professional positions at the foundation’s Manhattan headquarters and Ford was among the first employers in the country to implement paid paternal leave.

“His motto was ‘We are the R & D function of society,’” Henry Schacht, who was chairman of the Ford Foundation board of trustees during part of Mr. Thomas’s tenure, said in an interview. “He was perfectly prepared to take the risk that some of those investments would fail because that’s how you move forward.”

After Ford, Thomas served on the board of the TFF Study Group, a nonprofit institution assisting development in South Africa; he was chairman of the nonprofit the Sept.11 fund, and worked with the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund, managing its American office.

Thomas also helped to establish the Local Initiative Support Corp., a nonprofit supporter of many neighborhood revitalization drives across America.

Thomas is survived by his second wife, Kate Whitney; his sons, Kyle and Keith; his daughters, Kerrie Thomas-Armstrong and Hilary Thomas-Lake; his stepchildren, Andrea Haddad, Lulie Haddad, and Laura Whitney-Thomas; 16 grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren.

We extend our prayers and condolences to the family and friends of Franklin A. Thomas.