Mass Appeal #HipHop50 creative director Sacha Jenkins and Sally Berman’s photo exhibit documents Hip Hop’s growth from the streets of New York City to a worldwide movement.

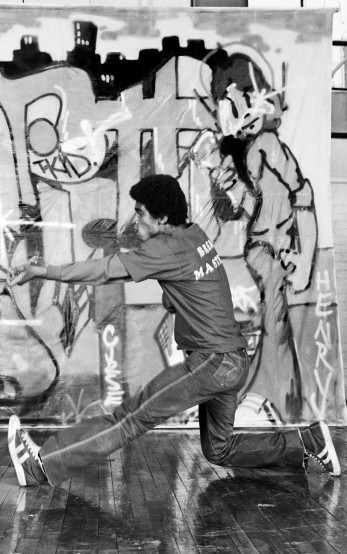

Sacha Jenkins, the former music editor of Vibe, is hip-hop's renaissance man. An artist of the highest order, the Queens, New York native is one of the foremost documentarians of the culture. As a writer, director and producer, his work had been dedicated to preserving the elements of hip hop—emceeing, deejaying, break dancing, graffiti, and beatboxing—and documenting its evolution as the most popular cultural expression in the world.

Launching his career in 1988, Jenkins published his first 'zine, Graphic Scenes & Xplicit Language, which is one of the earliest magazines promoting graffiti art. In 1992, he and Haji Akhigbade created Beat-Down Newspaper, one of the first hip-hop newspapers; and then, in 1994, he went on to co-found Ego Trip magazine, an iconic publication with Elliot Wilson.

Currently, he is the creative director of Mass Appeal where he leads the #HipHop50 initiative, which is a 3-year celebration with original films and experiences leading up to the 50th anniversary of hip hop that's being commemorated this year. In honor of the anniversary, Jenkins has executive produced Wu-Tang Clan: Of Mics and Men, Bitchin:' The Sound and Fury of Rick James, Cypress Hill: Insane In The Brain, and Supreme Team, all on Showtime. For Apple TV, he directed Louis Armstrong: Black and Blues, which was released in 2022.

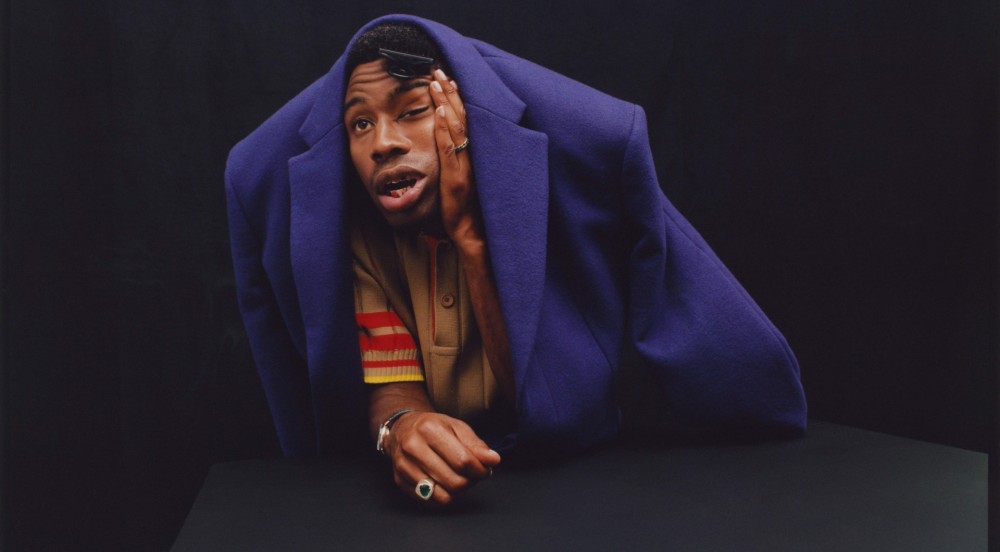

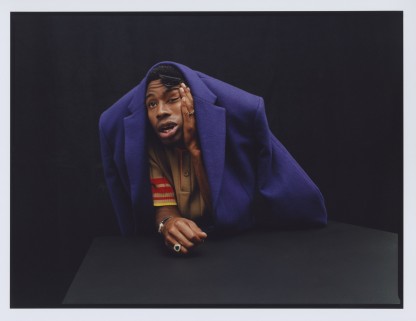

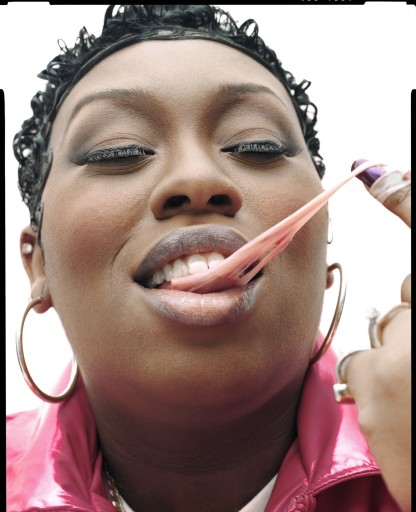

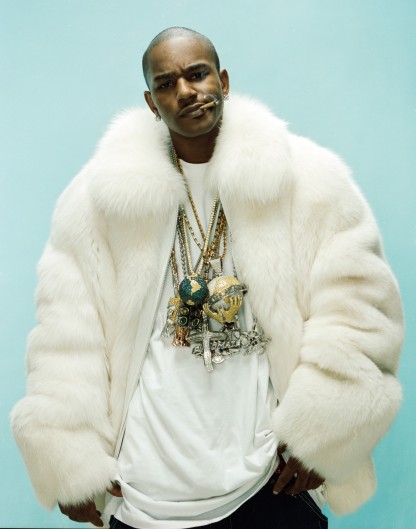

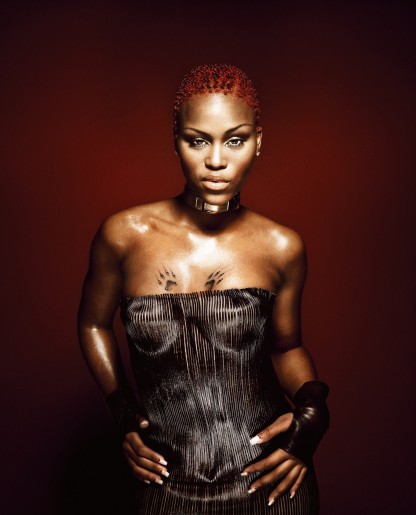

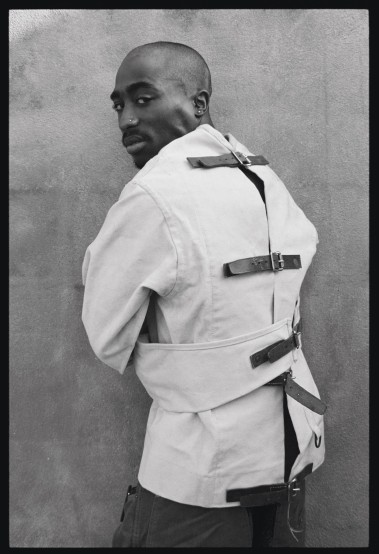

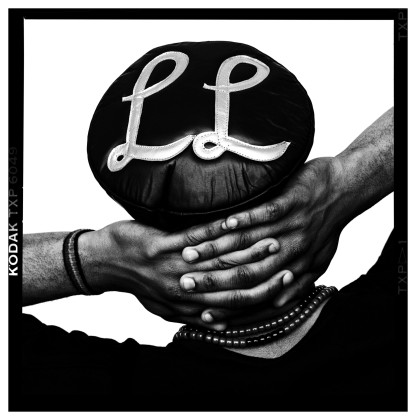

On his latest project, Jenkins along with Sally Berman curated Fotografiska's Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious exhibition, which is on view at the Fotografiska Museum in New York through May 21, 2023. The collection of photographs shows the movement from its embryonic stages in the streets of New York City and its growth all over the world.

EBONY spoke with Jenkins about curating the exhibit, commemorating the 50th anniversary of hip hop and what he believes the future has in store for the culture.

EBONY: What was the idea behind the name of the exhibit?

Sacha Jenkins: There was a time when hip hop wasn't conscious of itself at the time and then it became conscious of itself. We started to see ourselves and understand ourselves through video, photography, and everything else. That's what this show represents but it's also an inside joke. You have to look at hip hop for what it is and its reaction to an environment. I just did a film about Louis Armstrong for Apple, I made a film about the Wu-Tang Clan, I made a film about Rick James, and I'll tell you that hip hop, jazz and blues, it's almost the same thing. Louis Armstrong went to jail for having a gun at 14 years old. So while we love hip hop because it's beautiful, joyful, and transformative, we also have to recognize that it's a reflection of the environment. Through hip hop, we can learn a lot about what's going on in our communities and what needs to change. So while there are many aspirational things, sometimes it's not as conscious as it could be.

When hip hop started to crossover and began to have musicians and personalities, and started to get recognized in movies and videos, eventually, it became conscious of itself and started to understand that there was an aesthetic that we had built as kids in New York City that was completely neglected. Nas and I went to the same junior high and we were given the same route. We were told by our guidance counselors that we should go to vocational school. What if Nas would have gone to vocational school? We wouldn't have had the great art that we have from him today.

Curating an exhibit is a massive undertaking and Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious has been a labor of love for you. How long did it take you to complete the project?

We got everything together in about six months. It took a lot of photographers and a lot of photography. Sally Berman, who was working with me, is a professional photo editor and she brought a lot to the table. But it was a lot man.

The photos in the exhibit are incredible. Where did all the images come from?

The photos came from all over the world. A lot of shots were actually from California but there were some from overseas as well, so it was really a mixed bag.

In your view, why is this exhibition essential to the rollout of all the projects you've worked on in celebration of #HipHop50?

It's foundational. It tells the story of where hip hop comes from and where it's going. So to be able to lay out that kind of trajectory through photography, I think sets the stage for all the other things that are to come to commemorate the 50th anniversary.

From watching hip hop emerge in the parks of New York neighborhoods to becoming a worldwide phenomenon, how astounded are you at the culture’s continual evolution?

You know, when we were kids, it was something we did in addition to playing stickball, handball, football and basketball. It was just a part of our lives, of our existence, and of our identity. We had no aspirations or no idea that it would become what it's become, so it's pretty amazing to see what the culture has evolved into.

Hip hop is many things and I wouldn't be here today without it. I went to the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University on the strength of my knowledge of graffiti art, because I was able to make the connection between an arrow that was painted on the side of the train in 1973 to a logo created by an art director in San Francisco for an NFL team. So hip hop is extremely fluid and it gave social capital to many of us who didn't have capital. Hip hop is for everyone and that's a beautiful thing.

Lastly, for those who will see the exhibit and may not be aware of the origins of hip hop, what do you want them they take away from it?

Hip hop is not just about the music, it's about identity, it's about culture, it's about people. If it wasn't for the people, there'd be no hip hop. The music is always a reflection of the people and the environment. So if you understand the people, you can get a sense of what might be happening during the music and in the culture. I want people who will come to the exhibit to understand that hip hop is about people because that’s the most important thing.

Check out more images from Fotografiska's 'Hip-Hop: Conscious, Unconscious' Photo Exhibit below.