Korey Wise, Kevin Richardson, Raymond Santana, Antron McCray, and Yusef Salaam.

The Central Park Five, later and more respectfully known as the Exonerated Five following their exoneration in 2002, have endured what many in this country could never fathom and may never have to conceptualize. When one is significantly wronged and denied justice, as the Exonerated Five were in their adolescence, it takes an immense level of fortitude to not develop a cold, resentful outlook on the same world responsible for that misdeed. This is especially true when the repulsive nature of racism and systemic inequity rears its vile head to validate the stripping of the humanity of Black and Brown bodies. Wrongfully convicted and accused of the assault of Trisha Meili in New York City in 1989, the Exonerated Five were coerced into disgustingly long prison sentences at the fragile ages of 14 (Richardson and Santana), 15 (McCray and Salaam), and 16 (Wise).

Following the success of the Ava Duvernay directed Netflix series When They See Us, the five men impacted have had a renewed platform to share their stories in a way that only they can. In a deep contrast from the media attention they received as teenagers, they have since robustly garnered attention both as a collective and from the vantage point of their individual experiences in prison. Through their journeys, the public has been fortunate to see the duality of the Exonerated Five regaining and experiencing their rightful freedom while grieving and reckoning with time lost over an unnecessary sacrifice. Since their exoneration these men have been on a path toward true healing, happening in their own time and unique fashion. This path has consisted of milestones such as starting families, committing to the betterment of Black and Brown communities, going on to receive honorary degrees at prestigious universities, and even running for Senate seats in the communities that birthed them.

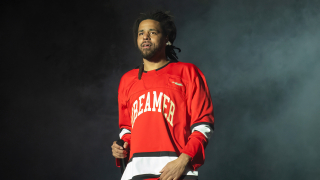

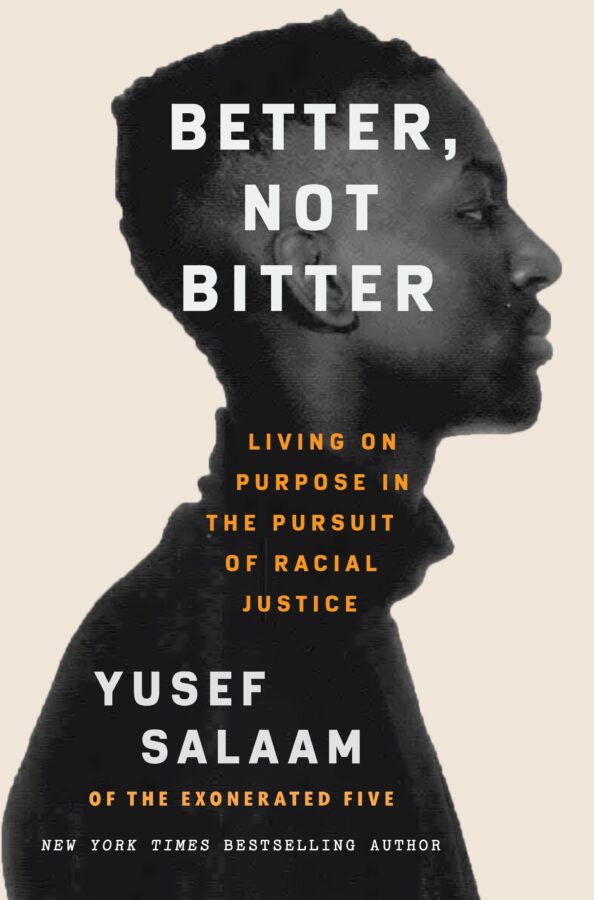

In the personal memoir Better, Not Bitter: Living on Purpose in the Pursuit of Racial Justice, Dr. Yusef Salaam boldly and proudly shares the foundational principles that guided him in his youth, through his wrongful imprisonment and today, where he shares his light for others to bear witness to and learn as an activist and motivational speaker. Simultaneously, Salaam offers both a critique of the prison industrial complex as it operates today and a solution for reconstructing this system as one that prioritizes oppression to one rooted in communal accountability and restorative justice.

EBONY was honored to sit down with and hear the reflections of Dr. Yusef Salaam about his life experiences and lessons learned in “Better, Not Bitter.”

EBONY: What was the catalyst for telling your story and your experience with the prison industrial complex in this manner?

Dr. YUSEF SALAAM: Well, you know, the story of the Central Park Five, as we were once known, and as was shown in When They See Us, and of course, in the documentary, the Central Park Five by Ken Burns. Burns really did a deep dive and broad overview of the story of the five of us, but there was the missing link of the individual stories. I say missing link only because there was a moment where we got the opportunity to really dive into Korey’s story and how terrible and tragic it was to experience that. Right? And when you look at the rest of the stories, especially my story, you get the sense that we were okay during that process and miraculously survived through some sense of grace by the Creator. But you needed to know what that was. For me, I wanted to tell that story, and I wanted to tell it in such a way that people got the understanding that it wasn't just about this thing that happened to me, or this thing that happened to the five of us; it was about telling the story of being a Black person in America and what that reality is like. How tragic it is that we walk around with this color of our skin and we are always seen as a crime. I wanted to not only tell that story but I wanted to also talk about how we can use our God-given power to really bounce back from anything, because we were born on purpose, and with a purpose.

There are many people in this country who have been deeply affected by the prison industrial complex in our country and who may not be able to recover from such a situation, or they may end up with the bitterness you speak of in the book. As an activist and abolitionist, how have you consciously chosen to be better and not bitter?

I would say in that process, and I call it a process on purpose because you have to literally go into a mode of Sankofa—in order to move forward, you have to go back and remember that we all stand on the shoulders of great people. We come from a great history of kings, queens, princesses, and princes. We also come from a great history of thinkers of movers and shakers of people who have been down underneath the ground. You know, as some people call it, we've been in the mud, and we've come out of the mud, and we made something of ourselves. I'm talking about as far back as we can remember to as more recent historically documented times, like chattel slavery to the creation of things like Black Wall Street. I say that to, to remind people that we stand on the shoulders of giants, and some of those giants just recently transitioned. Folks like John Lewis and Nelson Mandela. I think about people like that, including my great “she-ro”, Dr. Maya Angelou, because I got the opportunity to not just hear the words, but I got the opportunity to mull it over for years upon years.

Hearing Nelson Mandela say that he had to leave anger and bitterness in the prison as taking it with him meant that it would destroy him was powerful for me. In a situation like that where they were run over by the system, anyone would seek revenge. The wisest of us understand that people who harm you often have already moved past that point of harming you, and they're living their lives. We're the ones stuck in that moment. We're stuck in time. In my case, it was 15 years old Yusef Salaam, right? Then when I came home from prison, I was now 20-plus years old, but I was still stuck as a fifteen-year-old Yusef Salaam. All of the work that I had been doing in the prison was focused around theory. I had to figure out how to take that theory and now make it so. I hadn't yet heard the words of the great philosopher Cardi B “knock me down nine times, I'll get up ten.” But I did hear the words of Les Brown, who said, it's not a matter of if you fall in life but when you fall try to land on your back because if you can look up, you can get up.

Following your release and in your journey to alleviate the bitterness, what became your ultimate inspiration and driving force to leave it behind?

The words of Dr. Maya Angelou so strongly rang through my ears frequently. When she said, “you should be angry, but you must not be bitter.” That bitterness is like a cancer. It eats upon the host and it doesn't do anything to the object of his displeasure. Then she teaches us to question how we can use that very thing that is trying to make us bitter and turn it into gold? We become alchemists through the process. She said use that anger—you dance it, you march it, you vote, you do everything about it. Then she said you talk, and never stop talking it.

I've found that the process of finding purpose and living on purpose and living in a way that you live every day so that you only die once is a choice. It's a choice that you get the opportunity to live fully so that you can die empty and that you get the opportunity to say I'm not going to wait for someday to come—that someday is now. Then that isolated island of bitterness becomes the place where all of the gold, all of the diamonds, all of the wealth of the world, is found. Oftentimes, that place becomes a graveyard because it's a place that people have let life pass and slip through their hands. We’ve got to do as much as we can, live as well and unapologetically as we can. Even when the spiked wheels of justice run you over, get up and realize that you're still alive. Those wounds really do become battle scars. They have stories to tell. You can use them to not only tell your children how they have to stand up through adversity, but also with others who support you in the movement and get the opportunity to look at you as an example. They find strength in the fact that you are still standing and that's important.

As you mention in Better, Not Bitter, Black and Brown folks must realize our own collective power and use it to harvest something great. We’ve seen this happen over the past year as our communities have been holding space for conversations that will open up a greater dialogue for structural change with topics such as defunding the police and prison abolition. How would you like people to reimagine what they think of when they think of the prison industrial complex in order to imagine something great?

I think about it from the perspective of systems. We are in the era where we've heard new language being used around what we need as communities. A lot of that new language is very scary to people who are part of the establishment. And furthermore, it's scary to us as well. However, we know that what we know we need is not what we have right now. What we currently have is that we can be one of the most recognized elite members of society and we can still be harassed, at best, and we could be harmed or murdered in the communities that we come from. We know far too often that we've been taught that you're going to be dead or in jail before you reach the age of 21. Very rarely has anyone ever said to themselves “who gave us that thought?” "Who planted that seed of thought in our minds that we carry out?" Once we become conscious that we have not constructed that way of thinking ourselves, we then have the opportunity to remove the box that someone else has placed us in.

We look at the sides of the cop cars in New York City and cop cars around the nation, and they all have some semblance of the same wording “to protect and serve.” That is a very noble thing. As a matter of fact, it's a noble profession to go into if you are there on purpose and on your square saying “what do I do God with my life?” —and your soul is vibrating in such a way that is telling you to protect and serve people. We want those specific people to protect and serve our communities. We don't want criminals to police us. We don't want people who harm people on purpose to police us. That's what we've been seeing over and over and over again. So in today's understanding of what it is that we need and want, we want a system that is for the people, and perhaps, by the people. A system that represents a kaleidoscope of the human family and no longer upholds protections afforded to some that are not afforded to others. James Baldwin was so right when he said that in America we live in a state where to be relatively conscious puts you in a state of rage all the time. Here, we are African Americans, for the most part, where we are African without memory and we are American without privilege. Because of this, we've been living in the divided States of America. We've been trying to figure out how we can become one. Unfortunately, there has been this concerted effort that I call the true fight. The true fight that we're fighting against is not just a fight against racism; it's not a fight against sexism; it's not a fight against Islamophobia. All of those things are rocks that are being thrown at us. What we're really fighting is like what Bob Marley said in one of his beautiful songs—we're fighting against spiritual wickedness in high and low places.

To have a deep consciousness of our current conditions as a community can either feel rage-inducing, overwhelming or like an immense sense of passion. With the work that you are doing paired with your life experience, there must be moments when that rage may seem to be too much. When you feel that rage or feel like you're slipping back into bitterness, how do you find joy and remember the beauty and the light in this time?

I am Muslim. In my faith, we imagine somebody just placing boxes and weights and all kinds of things on your shoulder and head and walking around life every day with this on your shoulders. How much weight would that be? So as a Muslim, we are taught that we have to pray five times a day. With praying, you have to bow and you have to prostrate—so imagine all of those boxes just falling off of you as you do so. I'm saying that because I get the opportunity to understand that through prayer, especially while I was in prison, I understood this on a really powerful level. Prayer is when you are talking to God. You get the opportunity to talk to God and tell God everything that is going on with your life. When you then couple that with meditation, you are learning to be still in order to listen. I'm not talking necessarily about being in a state of non-movement. In prison, you could not always just sit down. You had to move around. You had to walk around people who might be killers and murderers and rapists right—so you had to walk and meditate. You had to eat and meditate. You had to be cognizant of what it was that you were putting in your mind through what you saw and putting in your heart through which you hear and read. And so communicating with the Creator is important, because you can tell God anything.

God says in the Quran that he does not change the condition of a people until they change themselves. It's about really becoming the change. There are more conversations being held around the dining room table or on Zoom meetings now than there were before COVID-19. We're hearing the language of abolition and such because we absolutely need abolition. We need to build a new system with new bricks because what we have is not conducive to living a full life. But on the other hand, we know that we can't live in a state of lawlessness. We have to live in a system that is life-given and that's life-affirming. One that teaches you that you were born on purpose, and with a purpose that gives you the opportunity to look around your community, and where other people have seen the worst of life, you see the best and abundant opportunity. A system that says that you matter and that you have a voice.

How do we change the system? We do so by having the people who have been impacted articulate the situational nature of the system. Again, James Baldwin said that the person who is a victim and who can articulate the situation ceases to be the victim. They now become a threat to the old ways of being. As we change, we need a system that will change with us.

What is your greatest hope that people take away from reading your own personal story as a part of the greater narrative of the Exonerated Five?

When we were born, we were one of over 400 million options. My hope is that we find that purpose. My hope is that as we are struggling and groping through the darkness of life, we begin to understand that sometimes we have to activate the light inside of us in order to see the way. I know that all that I’ve experienced is not for nothing. I know that even being run over by the spiked wheels of justice was to teach me how to get up. I was young enough to realize that I still had my faculties and that I could still tell myself that I was born on purpose. My hope is for others to realize that too and step into that purpose.